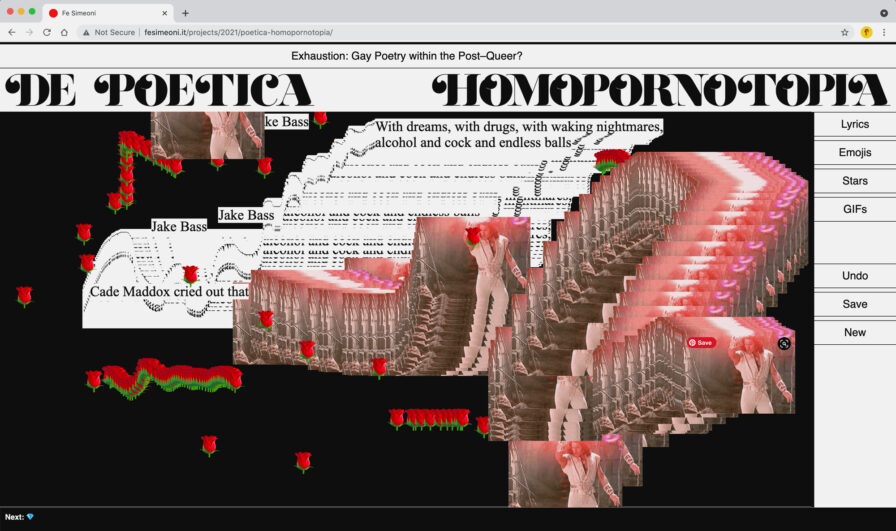

This interactive art work and text have been created as a part of the Interactive Poetry -course at Aalto University during spring 2021. Written and created by Federico Simeoni.

Teokseen | Enter the artwork

Mythical Memes for Homonormative Post-Queer Times

The gay revolution has been an identitarian issue, born on the need for a better label than the sinful sodomy. As Leo Bersani argues, the step further has been the queer: often accused of being anti-gay [1], this cultural revolution challenged the categorizations of sexuality. The progress in the research for the cure of AIDS and the possibility of a normal living albeit the illness has erased the sense of doom and melancholia of the past decades. Furthermore, in western society, queer people have witnessed a progressive demise of the social stigma for not having a heteronormative behavior: paraphrasing Lawrence Schehr, from the hate for the family, we are facing now a nice indifference [2]. Consequently, this happy queer-normativity is now leading towards post-queer issues: being gay is an exhausted concept.

The twenty-first century, indeed, is the era of global instant connections. Claire Boyle claims that the endless potential of knowing any remote other puts the virtual at the center of the post-queer: overcoming the rigidity of taxonomy, the individual becomes “the realm of the potential.” The post-queer human does live in physical geography, but also in a digital flow of distant individuals, losing the contours with the others and the machine. [3] Referring to Donna Haraway, the plugged-in subject operates “within the paradigm of the post-human, the space of the cyborg.”

“I was gay-born online” asserted Joel Simkhai, the Israeli-American tech entrepreneur founder of Grindr. It is in this multi-layered physical and digital space that the heart of gay life lies. Andrés Jaque notes that, freed from the need for anonymity, the new happy homonormativity is based on a flow of standardized images of fashionable males in porn-alike poses located in designed interiors. [4] Using Gilles Deleuzes terminology, Grindr users are not machines désirantes anymore, but désirées, for they sell themselves as objects validated by the system. [2]

Guillaume Dustan defines the physical, mental, and virtual geography where queer people live as a pornotopia: a place where “a set of predictable images and a minimalism of language replace the narrative of self and other”. [3] Here relationships between people are not mediated by gay literature, but porn. Being gay has always been connected with agreeing of performing a sexual role, that comes out of porn or pop music. As Claire Boyle argues, “this is a world in which plot is accidental, in which the next lay is around the corner, in which all men are gay and well-endowed, in which pleasure goes beyond language to the primal, and in which the only real activity is sex.” [2] The users living in these pornotopias do not present themselves as people, but more as the incarnation of one stereotype of an agreed range.

The result is a diffuse feeling of emotional numbness, like the one depicted by TS Eliot in The Waste Land, a vivid juxtaposition between a lyrical past and a squalid unpoetic present. The so-called mythic method prescribes countless literary and epic references for the description of the current human condition. [5] Using Alessandro Serpieri’s words, Eliot is more focused on “putting into relation: subject and object, present and past, reality and myth, text and text.” [6]

This technique can be relatable to situationist détournement. Guy Debord and Gill J Wolman suggested that “the discoveries of modern poetry regarding the analogical structure of images demonstrate that when two objects are brought together, no matter how far apart from their original contexts may be, a relationship is always formed. Restricting oneself to a personal arrangement of words is mere convention.” [7] The mutual interference of two different worlds or the juxtaposition of two independent expressions supersedes the original elements and produces a greater efficacy.

As Valentina Tanni argues along with Vuk Ćosić’s words, in our present world of instant digital communication, people have incorporated in their daily routine all the conceptual instruments created by situationists and conceptualists. [8] What we see scrolling in our feeds eighty years ago would have been the most innovative artistic act. Darren Wershler calls it “conceptualism in the wild.” [9]

Valentina Tanni goes on to argue that the real participation of the spectator has not been reached via designing interfaces, inviting the public to press buttons or to navigate a hypertext. Neither relational art managed to be a mass phenomenon since it only spoke to people inside the art system. The gradual inclusion of the public in the work of art happened with the disappearance of the line between author and spectator. Indeed, as Walter Benjamin predicted, “the reader is always ready to become an author” [10] and the internet gave this possibility to an enormous amount of people.

“In a world where everything is documented, searchable, downloadable, and remixable, revisionism is a perpetual process that includes historical and contemporary events.” [8] There must be somebody who gave birth to a memetic thread, but the anonymity, rapidity, virality, and referentiality of the phenomenon make the quest for an author out of the Zeitgeist. Like Debord and Wolman asserted in 1956, “plagiarism is necessary: progress implies it.” [7] As also Leonardo Flores explains, “people are stepping away from the page to write over images, for they have context and set up situations:” they activate multi-modal metaphors. [11]

In these terms, meme production has certain connections with the Homeric Question. Andrew Bennett asserts that in the oral epic tradition every performance constitutes a new composition, for the singer both repeats and alters a set of variable texts repeated and altered by other singers. He then quotes Albert Lord for expressing the contemporary frustration regarding the impossibility of constructing an ideal text or seeking an original, remaining dissatisfied with an ever-changing phenomenon. [12]

De Poetica Pornotopia aims to express the feeling of the gay community of the Western World when it realizes that there is no pain left to cry. Using a combination between the mythic and the memetic method, the emotional profoundness of the past is related to the contemporary shallowness of homonormative pop and porn references. In a détournament, lyrics are alienated by the images they are put on by a user who is neither public nor author, but a rhapsode.

Notes

[1] Leo Bersani, Homos (Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press, 1996).

[2] Lawrence Schehr, “Topographies of Queer Popular Culture,” in French Postmodern Masculinities (Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2009).

[3] Clair Boyle, “Post-Queer (Un)Made in France?,” Paragraph 35, no. 2 (2012)

[4] Andrés Jaque, “Grindr Archiurbanism,” Log 41 (2017)

[5] TS Eliot, “Ulysses, Order and Myth”, The Dial (November 1923)

[6] Alessandro Serpieri, “Introduzione” in TS Eliot, La terra desolata (Bologna, IT: Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, 1985).

[7] Guy Debord and Gill J Wolman, “Mode d’emploi du détournement,” Les levres nues 8 (1956).

[8] Valentina Tanni, Memestetica. Il settembre eterno dell’arte (Brescia, IT: Nero Edizioni, 2020).

[9] Darren Wershler, “Best Before Date,” Alienated (4th April 2012)

[10] Walter Benjamin, L’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua riproducibilità tecnica (Torino, IT: Einaudi, 1936)

[11] Leonardo Flores, Turning the Page: Latinx Born-Digital Literature (US Naval Academy, Annapolis, US, 25 February 2020)

[12] Andrew Bennett, “Authority, Ownership, Originality,” in The Author (London, UK: Routledge, 2005)